ACG Insights: Tariffs and Trade

(Download the Full Report HERE)

Executive Summary

- Tariffs and trade policy are back in the news as President-elect Trump prepares for a second term.

- Tariffs equate to a tax on imports, paid by the importer to the government, levied for various policy goals like protecting domestic industry or economic leverage.

- For the economy, tariffs on balance are generally associated with lower GDP growth, higher prices, and less competition.

- For markets, reaction to tariff policy was muted during Trump’s first term, but risks are prevalent should campaign promises translate into actual policy.

What/Why/How on Tariffs

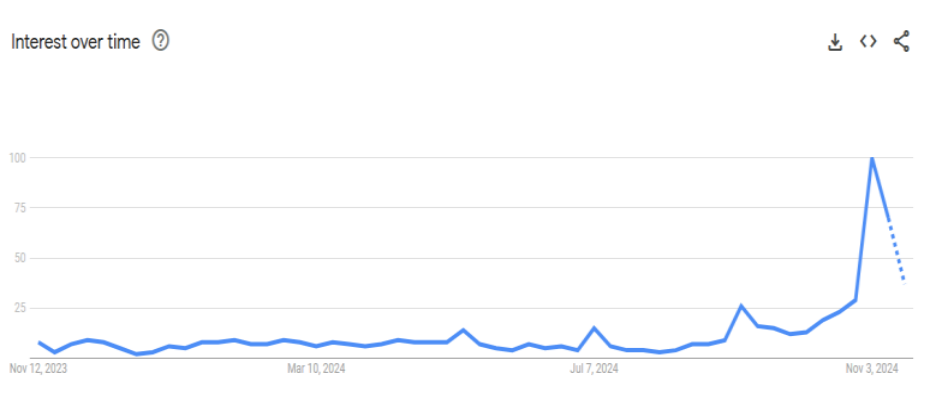

We will stay as far away as possible from politics, other than to say that tariffs are back in the headlines after campaign season and the recent US presidential election (Exhibit 1). The bigger question for this discussion is to consider how trade policy may impact investment allocations. The unsatisfying answer for investors is that the impact is extremely murky. No one really knows what policies will come to fruition and how markets will react, but it is still worth considering the range of outcomes and portfolio implications.

Exhibit 1: Google Searches for “Tariffs”1

Before moving to investment themes, it is worth a refresh on tariff basics. In short, a tariff is simply a tax on imported goods, paid to the government by the company importing the goods. Tariffs are generally administered as a percentage of the value of the imported goods, but, per the Council on Foreign Relations: “There are also “specific tariffs,” which are charged as a fixed amount on each imported good (for example, $2 per shirt) and “tariff-rate quotas,” which are tariffs that kick in or rise significantly after a certain level of imports is reached (e.g., fifty thousand tons of sugar)”.2

In the US, tariffs are collected by the customs service at the point of entry, usually a coastal port. As a crude example say the US levies a 10% duty on all olive oil from Italy. A grocery chain, maybe Kroger, now pays an extra $10 (to the government, not the olive oil manufacturer) for every $100 of Italian olive oil they want to keep on the shelves. Kroger now faces choices including passing on price increases to customers to maintain margins or re-shaping their product offerings. For certain products, companies can also alter supply chains to move production to countries without tariff restrictions. We saw this process in practice starting in 2017 when imports from China started to shift to countries like Mexico, Vietnam, and Taiwan.3

To read the Full Report, click HERE.

Sources:

- Google Trends (one year timeframe)

- Council on Foreign Relations

- Wall Street Journal

- World Bank

- Tax Foundation

- JPMorgan

- Tax Policy Center

- Fordham Law School

Connect With Us

Interested in learning more? The professional advisors at ACG are happy to answer any questions you

have. Contact us to discuss solutions and discover how our advisors bring value to your institution.